In my last post, I wrote that most people don’t know how to construct a good story.

Luckily, a game master does not have to be a good storyteller to to run an enjoyable game.

I find that setting up a situation with an engaging problem, asking the players what their characters do, using the game system to determine the outcome of the players choices and moving forward with the logical consequences of what those outcomes mean will produce an experience that is more satisfying and with much less effort than any pre-plotted story.

That said, you can benefit from understanding the basic elements of story because they are also the basic elements of role-playing games.

Understanding those parts of story can help you to understand how they work in games.

Why do role-playing games and stories share certain properties?

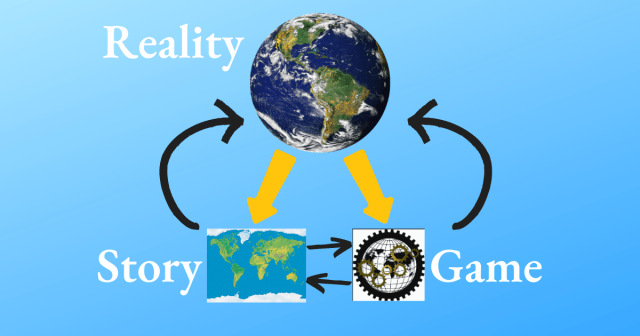

Stories and games are two related but different ways of understanding reality. A story is a map of reality and a game is a model of reality.

Both can tell us something about the world we’re looking at because they are expressions of the same thing. The map is fixed. It tells us what’s where at a fixed moment in time. A model is dynamic. It allows us to experiment by messing with one part of the model and watching to find out how the rest responds.

Many famous fiction writers have called stories “a lie that tells the truth” or give the advice of “being honest” in your storytelling. Writers have to include some properties of the real world in their stories for them to resonate with the audience. This foundation in reality is why a story can “ring true” or make it possible to “suspend our disbelieve.”

There’s enough reality embedded in them to give them a sense of truth or to communicate a truth the author wants to tell the reader.

Games are interactive models. RPGs came from experiments with wargames. Wargames model a narrow piece of reality as with as much fidelity as the designers can muster. The further from reality they diverge, the less useful they are as a way to understand war and its conduct.

Roleplaying games derive from wargames but are closer to stories in that they have some elements of un-truth mixed in with the model of reality.

Games and stories are conceptual tools humans use to make sense of the complex universe we live in.

Even though stories and roleplaying games aren’t the same thing; they have the same origin. They are representations of human experience. Having that same origin point, they have some components in common. Understanding the components of stories helps us to understand RPGs and vice versa. Understanding stories and games can help us to get a better understanding of reality.

The parts that story and role-playing games have in common

Role-playing games and stories have these things in common.

- Characters

- The Character’s Objectives

- Obstacles preventing the character from achieving the objective

- Choices or actions the character takes to achieve their objective

- The outcome of those choices or actions

The characters are the people we follow in the story, even if that “person” is Brer Rabbit, a lion or a replicant.

The objective is whatever the characters are trying to achieve. Blowing up the Death Star, killing Rasputin, or getting back to Kansas are objectives.

The obstacle is the thing preventing the characters from achieving their objective. The Harkonnens, a blizzard, or evil cultists trying to bring back Nyarlahotep are obstacles.

The actions or choices a character makes are the focus point of both stories and games. Taking the shot by using the Force instead of the targeting system, detonating the oxygen destroyer, or Romeo taking poison to join Juliet in death are actions and choices the character takes to overcome their obstacles on the way to their objectives.

Actions in combination with the other elements create the theme or the message of the story. You can have a character, an objective, and obstacle but if the character sits at home watching TV, then there is no story.

The outcome is result of the characters actions and choices to overcome the obstacles in their pursuit of an objective.

How we arrive at that outcome is the most important difference between stories and role-playing games.

Escalating Objective-Obstacle Encounter

The fundamental unit of a story is a scene. A story is a series of scenes where the characters progressively work toward their goals.

Each scene has the same structure of a story.

character->objective->obstacle->-action->outcome

“The encounter” is the basic unit of an adventure structure.

An encounter in an RPG has the same basic structure of a scene. A string of related encounters is an adventure. A string of related adventures is a campaign.

The characters have an objective. There is an obstacle to that objective. The players make choices. The game mechanisms determine the result of those choices. They go onto the next encounter until all the encounters in the adventure have been overcome, the characters die, or the players withdraw from the adventure.

Knowing is half the battle

Having a solid grasp of these components of both story and role-playing game scenarios has helped me to create adventures and campaigns and they help me when I need to improvise an encounter.

Every adventure has a primary objective and obstacle. The dragon’s hoard is the objective. The dragon is the obstacle.

Every encounter has an objective and obstacle. Getting through the door intact is the objective. Avoiding or disarming the trap is the obstacle.

If a situation doesn’t have an obstacle, then it isn’t an encounter. If the door is unlocked, not trapped, and easily opened, then it isn’t an encounter. It’s a transition between encounters or exposition that tells the players about what is beyond the door.

If players do something I don’t expect then I can improvise an encounter.

The party’s objective is to get information. I improvise an obstacle.

The sage they consult is reluctant to tell them what they want to know because it is dangerous information not meant for mortals. The party has to come up with a way to overcome the sage’s fear or go in ignorant of what they face.

You don’t have to be a good storyteller to be a good game master.

The idea I hope you take away from this post is that stories have some basic elements in common with roleplaying games and understanding how they work in stories can help you employ them in your games.

Once a game master understands the basics, they can layer on other techniques borrowed from storytelling that enhance the game experience without turning it into an interactive narrative, but you can have a good time without those methods. They aren’t required to run a fun game and are advanced skills that you can pick up over time.

You must be logged in to post a comment.